history

a century of partnership

For more than a century, Chevron and the City of Richmond have shared a proud heritage. By working together, we can create new opportunities for residents and help the community reach its greatest potential.

the early years

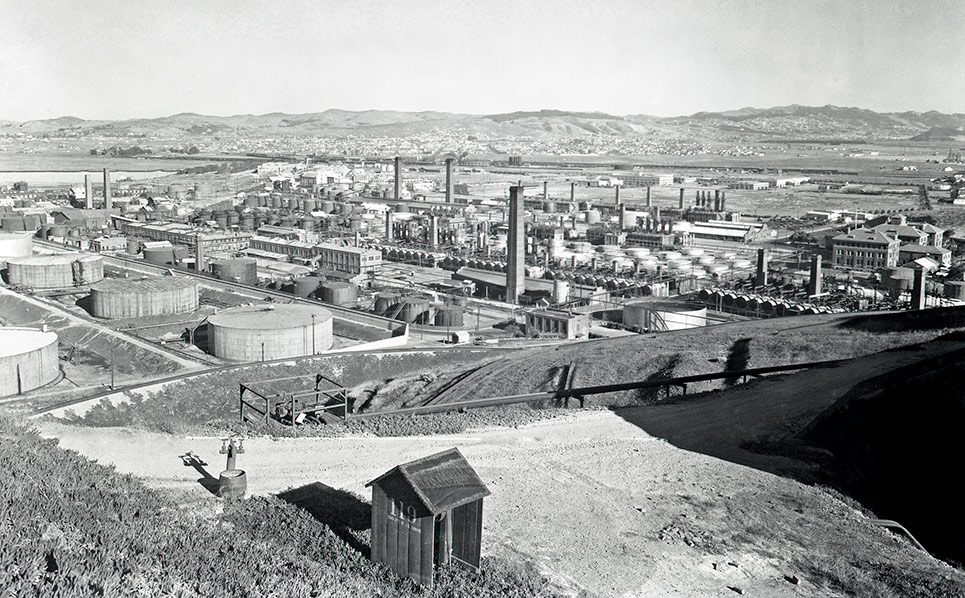

Built on a peninsula of low hills rising from San Francisco Bay, the refinery became the West Coast’s largest and most advanced plant upon its completion in July 1902. A complex of red brick buildings, the new plant contained 19 stills that could process 10,000 barrels of crude a day and had a tankage capacity of 185,000 barrels in its first year of operation.

Chevron’s earliest predecessor, the Pacific Coast Oil Company (PCO), needed a refinery large enough to develop its fuel oil business and capable of processing light as well as heavy crudes from Southern California fields. Manufacturing supervisor William Rheem scouted the Bay Area for a location that would accommodate the new refinery and pipeline terminal. He found the ideal site along a dusty country road that terminated near a tiny railroad settlement called East Yards. At a tract of land just north of the village stretched 600 acres of rolling abandoned farmland.

In October 1901, construction began. An abandoned farmhouse served as the original headquarters for the Chevron Richmond staff during the plant’s early construction phase. By June 1902, the first cargo of crude oil was delivered to the Richmond wharf. This ability to employ marine transportation became a significant factor in the refinery’s growth.

On July 3, 1902, the refinery came to life as the first oil flowed into the new stills and the fires were lit. Although the refinery was fully operational, growing pains remained. Many early employees slept in tents until permanent bunkhouses were constructed. By 1903, an electric trolley line, the first in Contra Costa County, began to run between the refinery and the wharf.

The refinery had an original staff of 80 employees, including engineers, mechanics, technicians, inspectors and managers who had come together from within California and across the nation to operate this refinery. Their presence transformed the small town of Richmond, which had just 200 occupants at that time. By 1905, when Richmond was incorporated, its population had grown to 2,150 residents. The town’s population mirrored that of the refinery workforce.

After coming out of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake with relatively limited damage, the refinery achieved an important milestone in 1907 when it developed Zerolene motor oil. At the time, Richmond was one of the largest refineries in the world. By 1914, as the world was on the brink of war, the output had reached 65,000 barrels a day.

Chevron’s earliest predecessor, the Pacific Coast Oil Company (PCO), needed a refinery large enough to develop its fuel oil business and capable of processing light as well as heavy crudes from Southern California fields. Manufacturing supervisor William Rheem scouted the Bay Area for a location that would accommodate the new refinery and pipeline terminal. He found the ideal site along a dusty country road that terminated near a tiny railroad settlement called East Yards. At a tract of land just north of the village stretched 600 acres of rolling abandoned farmland.

In October 1901, construction began. An abandoned farmhouse served as the original headquarters for the Chevron Richmond staff during the plant’s early construction phase. By June 1902, the first cargo of crude oil was delivered to the Richmond wharf. This ability to employ marine transportation became a significant factor in the refinery’s growth.

On July 3, 1902, the refinery came to life as the first oil flowed into the new stills and the fires were lit. Although the refinery was fully operational, growing pains remained. Many early employees slept in tents until permanent bunkhouses were constructed. By 1903, an electric trolley line, the first in Contra Costa County, began to run between the refinery and the wharf.

The refinery had an original staff of 80 employees, including engineers, mechanics, technicians, inspectors and managers who had come together from within California and across the nation to operate this refinery. Their presence transformed the small town of Richmond, which had just 200 occupants at that time. By 1905, when Richmond was incorporated, its population had grown to 2,150 residents. The town’s population mirrored that of the refinery workforce.

After coming out of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake with relatively limited damage, the refinery achieved an important milestone in 1907 when it developed Zerolene motor oil. At the time, Richmond was one of the largest refineries in the world. By 1914, as the world was on the brink of war, the output had reached 65,000 barrels a day.

growth through research and innovation

The automobile transformed society during the second decade of the 20th century. From 1914 to 1918, the number of passenger cars in the United States rose from 1.6 million to 5.6 million. This abrupt transformation intensified the demand for gasoline, lubricants and other petroleum products. Chevron Richmond became an increasingly valuable asset as Standard Oil Co. of California (Socal) adapted its product base to accommodate the growing popularity of the automobile and other means of transportation.

By 1915, the refinery employed 1,700 workers. Now spread across 435 acres, the plant included 117 stills with a capacity of 60,000 barrels a day. The products served markets throughout the Pacific Coast and other parts of the United States as well as points all around the globe.

In 1917, when the United States entered World War I, Richmond adapted to a new imperative. The refinery had a vital role to play in World War I because of the war effort’s dependency on fuel for trucks, tanks, tankers, trains, and planes.

Recognizing the importance of experimental as well as basic product research, the company introduced a well-equipped red brick laboratory building to the Richmond facility in 1919. Development manager Ralph A. Halloran’s emphasis on centralized, systematic research helped the department gain greater prestige in support of the company’s tenet, “Research First - Then Advertising,” which ensured that a product was thoroughly tested before being introduced to the public. By 1924, the laboratory’s staff grew to 75 skilled employees, who engaged in tests and experiments, not only to develop new uses for petroleum, but to improve existing processes.

During the Great Depression, the refinery made a significant contribution to the economic well-being of its employees and the City of Richmond by instituting a job-sharing program under which more than 3,000 workers, by sharing their work with others, were able to retain their jobs during the worst years of the Depression. One historian credited Socal and other companies for helping to maintain Richmond’s economic viability during this difficult time, stating: “the worst effects of the stagnant economy were certainly blunted by the ability of Richmond’s businesses to keep their factories running and their employees working.”

During this time, the refinery made many other investments to support the health and safety of the workforce. In 1915, the refinery opened an emergency hospital, at which employees were treated for accidents and injuries and received annual physical examinations. New employees received special instruction in safety measures and practices. In 1924, the refinery began devoting a portion of each foreman’s meeting to a discussion of safety. Eleven years later, the first edition of “Safety Broadcast,” a periodic refinery newsletter, gave employees the opportunity to read about safety.

The onset of World War II brought major changes to the refinery. Many employees left for service in the U.S. military. Close to 400 women joined the refinery workforce, many as operators in the plant’s new catalytic cracking unit. The refinery quickly shifted its focus from a peacetime economy to provide high-octane fuel and other products to meet military needs. The U.S. Secretaries of War and Navy and the Petroleum Administrator commended Socal’s California refineries for exceeding the production of aviation gasoline requested by the government. And in 1945, Chevron Richmond won its fifth U.S. Army-Navy “E” award for its support of the military effort.

By 1915, the refinery employed 1,700 workers. Now spread across 435 acres, the plant included 117 stills with a capacity of 60,000 barrels a day. The products served markets throughout the Pacific Coast and other parts of the United States as well as points all around the globe.

In 1917, when the United States entered World War I, Richmond adapted to a new imperative. The refinery had a vital role to play in World War I because of the war effort’s dependency on fuel for trucks, tanks, tankers, trains, and planes.

Recognizing the importance of experimental as well as basic product research, the company introduced a well-equipped red brick laboratory building to the Richmond facility in 1919. Development manager Ralph A. Halloran’s emphasis on centralized, systematic research helped the department gain greater prestige in support of the company’s tenet, “Research First - Then Advertising,” which ensured that a product was thoroughly tested before being introduced to the public. By 1924, the laboratory’s staff grew to 75 skilled employees, who engaged in tests and experiments, not only to develop new uses for petroleum, but to improve existing processes.

During the Great Depression, the refinery made a significant contribution to the economic well-being of its employees and the City of Richmond by instituting a job-sharing program under which more than 3,000 workers, by sharing their work with others, were able to retain their jobs during the worst years of the Depression. One historian credited Socal and other companies for helping to maintain Richmond’s economic viability during this difficult time, stating: “the worst effects of the stagnant economy were certainly blunted by the ability of Richmond’s businesses to keep their factories running and their employees working.”

During this time, the refinery made many other investments to support the health and safety of the workforce. In 1915, the refinery opened an emergency hospital, at which employees were treated for accidents and injuries and received annual physical examinations. New employees received special instruction in safety measures and practices. In 1924, the refinery began devoting a portion of each foreman’s meeting to a discussion of safety. Eleven years later, the first edition of “Safety Broadcast,” a periodic refinery newsletter, gave employees the opportunity to read about safety.

The onset of World War II brought major changes to the refinery. Many employees left for service in the U.S. military. Close to 400 women joined the refinery workforce, many as operators in the plant’s new catalytic cracking unit. The refinery quickly shifted its focus from a peacetime economy to provide high-octane fuel and other products to meet military needs. The U.S. Secretaries of War and Navy and the Petroleum Administrator commended Socal’s California refineries for exceeding the production of aviation gasoline requested by the government. And in 1945, Chevron Richmond won its fifth U.S. Army-Navy “E” award for its support of the military effort.

fueling the peace and protecting the environment

People around the world greeted the end of World War II with relief, enthusiasm and a return to normal life. Normality brought with it greater mobility and an increased demand for conveniences to simplify life. Both of these trends had major impacts for the oil industry at large and, specifically, for Chevron Richmond.

In 1946, Standard Oil Co. of California (Socal) began a long-range modernization and expansion of its refinery facilities that continued unabated for the next quarter century. Chevron Richmond, the company’s largest U.S. plant, experienced dramatic growth in its facilities.

In 1959, Socal made a major breakthrough when it developed the Isocracking process, in which a catalyst rearranged the existing molecules in heavy fuel oils, creating a new hydrogen atom that removed sulfur and converted the low-value fuel oils into gasoline and other high-yield products.

With new cars and machinery came a demand for new products. The postwar years were marked by a dramatic increase in demand for petrochemicals to serve as the building blocks for hundreds of essential consumer products. Socal became a leader in this fast-growing area and relied increasingly on Chevron Richmond to supply its petrochemical needs. By 1960, Chevron Richmond was one of the foremost sources of petroleum chemicals in the United States.

While the refinery expanded its operations, it retained its strong record for maintaining high safety and environmental standards. One safety milestone occurred in 1949, when Chevron Richmond employees completed 2 million work-hours without a lost-time accident. This exemplary record was consistent with the refinery’s long tradition of stressing safety.

Operating in an environmentally responsible manner has long been an important priority for the refinery. Over the years Socal invested many millions of dollars in pollution control facilities, many of which were installed long before mandatory measures were enacted, and always ensured that its installations were in full compliance with all air pollution control regulations. In 1960, the company allocated more than $20 million to suppress emission of pollutants at its Richmond and El Segundo, Calif., refineries.

Protecting people and the environment was a natural way of doing business for a refinery with deep roots in the Richmond community.

In 1946, Standard Oil Co. of California (Socal) began a long-range modernization and expansion of its refinery facilities that continued unabated for the next quarter century. Chevron Richmond, the company’s largest U.S. plant, experienced dramatic growth in its facilities.

In 1959, Socal made a major breakthrough when it developed the Isocracking process, in which a catalyst rearranged the existing molecules in heavy fuel oils, creating a new hydrogen atom that removed sulfur and converted the low-value fuel oils into gasoline and other high-yield products.

With new cars and machinery came a demand for new products. The postwar years were marked by a dramatic increase in demand for petrochemicals to serve as the building blocks for hundreds of essential consumer products. Socal became a leader in this fast-growing area and relied increasingly on Chevron Richmond to supply its petrochemical needs. By 1960, Chevron Richmond was one of the foremost sources of petroleum chemicals in the United States.

While the refinery expanded its operations, it retained its strong record for maintaining high safety and environmental standards. One safety milestone occurred in 1949, when Chevron Richmond employees completed 2 million work-hours without a lost-time accident. This exemplary record was consistent with the refinery’s long tradition of stressing safety.

Operating in an environmentally responsible manner has long been an important priority for the refinery. Over the years Socal invested many millions of dollars in pollution control facilities, many of which were installed long before mandatory measures were enacted, and always ensured that its installations were in full compliance with all air pollution control regulations. In 1960, the company allocated more than $20 million to suppress emission of pollutants at its Richmond and El Segundo, Calif., refineries.

Protecting people and the environment was a natural way of doing business for a refinery with deep roots in the Richmond community.

building a world-class organization

Now in its second century of operation, Chevron Richmond continues to rank among the major refineries in the United States. Its consistent growth has confirmed its significant place within Chevron’s worldwide manufacturing network. Throughout, it has also sustained a close relationship with the community and conducted its business in a socially and environmentally responsible manner.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the refinery was virtually transformed to produce higher-value, higher-volume fuels and lubricating oils and to comply with increasingly stringent state and federal policies. The refinery took significant strides to reduce air emissions and waste, treat water, and prevent oil spills.

The company substantially increased its capability to manufacture reduced-lead gasolines by installing new reforming capacity at Richmond and three other U.S. refineries in 1971.

In 1979, a worldwide shortage of crude oil, along with a shift in the availability of quality crudes, presented critical challenges to the company’s manufacturing operations. Chevron subsequently invested more than $2 million in its U.S. refineries, improving their flexibility for handling different types of crude oil, responding to changing product standards, installing energy conservation equipment, and complying with environmental or regulatory requirements.

Also in 1979, the Richmond Technology Center developed Techron, the first patented additive developed for engines running unleaded gasoline. Techron has been reformulated over the years to increasingly reduce emissions, keep vital engine components clean and preserve original engine performance by preventing harmful deposits.

During the 1980s, Chevron Richmond continued to grow and diversify. The refinery’s growth was mirrored by a steady increase in Richmond’s population from about approximately 70,000 in 1975 to 101,000 by 2003. Chevron (the city’s largest employer) and other companies supported sustained job creation and other economic benefits, which along with a harbor redevelopment project and new housing, contributed to the growth in Richmond.

The new century brought a major celebration: the 100th anniversary of Chevron Richmond in 2002. At the time of its centennial, the plant had over 1,300 employees and was spread over 2,900 acres.

As the refinery moves forward in its second century of operations, we continue to conduct our business as we have for more than a century, in a socially and environmentally responsible manner to benefit the community where we work.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the refinery was virtually transformed to produce higher-value, higher-volume fuels and lubricating oils and to comply with increasingly stringent state and federal policies. The refinery took significant strides to reduce air emissions and waste, treat water, and prevent oil spills.

The company substantially increased its capability to manufacture reduced-lead gasolines by installing new reforming capacity at Richmond and three other U.S. refineries in 1971.

In 1979, a worldwide shortage of crude oil, along with a shift in the availability of quality crudes, presented critical challenges to the company’s manufacturing operations. Chevron subsequently invested more than $2 million in its U.S. refineries, improving their flexibility for handling different types of crude oil, responding to changing product standards, installing energy conservation equipment, and complying with environmental or regulatory requirements.

Also in 1979, the Richmond Technology Center developed Techron, the first patented additive developed for engines running unleaded gasoline. Techron has been reformulated over the years to increasingly reduce emissions, keep vital engine components clean and preserve original engine performance by preventing harmful deposits.

During the 1980s, Chevron Richmond continued to grow and diversify. The refinery’s growth was mirrored by a steady increase in Richmond’s population from about approximately 70,000 in 1975 to 101,000 by 2003. Chevron (the city’s largest employer) and other companies supported sustained job creation and other economic benefits, which along with a harbor redevelopment project and new housing, contributed to the growth in Richmond.

The new century brought a major celebration: the 100th anniversary of Chevron Richmond in 2002. At the time of its centennial, the plant had over 1,300 employees and was spread over 2,900 acres.

As the refinery moves forward in its second century of operations, we continue to conduct our business as we have for more than a century, in a socially and environmentally responsible manner to benefit the community where we work.